Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967) begins his diaries on a Latin American journey by stating “[t]he person who wrote these notes passed away the moment his feet touched Argentine soil again. The person who reorganizes and polishes them, me, is no longer, at least I am not the person I once was. All this wandering around ‘Our America with a capital A’ has changed me more than I thought.”1 These lines allude to the road trip that Che undertook in 1952, accompanied by his friend Alberto Granado, on Alberto’s aged motorcycle, La Poderosa II (the Mighty One), to explore Latin America. The journey has also been depicted in Walter Salles’s film, The Motorcycle Diaries, where a significant sequence is dedicated to the duo’s visit to Machu Picchu, a spectacularly situated Inca royal retreat placed in the saddle between two mountain peaks.2 Considering the transformative nature of Che’s road trip and the role that the Inca ruins played in it, in this essay, I will compare the representation of Machu Picchu in the film as a captivating site with the way it is investigated in the book to highlight the film’s pop-cultural framing of Che’s transformative journey.

The Motorcycle Diaries book (1993) and film (2004)

On a 12-hour train trip back from Machu Picchu to Cuzco, Che describes the condition of third-class carriages that are reserved for local Indians as appalling. He adds:

of course, the tourists traveling in their comfortable rail coaches could only glean the vaguest idea of the conditions in which the Indians live, from the fast glimpses they catch as they speed past our train, which has stopped to let them pass. The fact that it was the U.S. archaeologist Bingham who discovered the ruins, and expounded his findings in easily accessible articles for the general public, means that Machu Picchu is by now very famous in that country to the north and the majority of North Americans visiting Peru come here.3

Che’s observation of tourists’ obliviousness to the actual living conditions of the Indigenous people as they journey to visit Machu Picchu for its allure and attraction may distinguish him as a traveler seeking to know the region, rather than a tourist merely indulging his senses. It is true that Che went on the expedition “to explore a continent we had only known in books,”4 but this was not the single motivation behind his journey. As Neil Archer explains in The Road Movie: In Search of Meaning, Che and Alberto “engage in a journey whose motivations are largely touristic, even exoticist (at a time when, before globalization and ubiquitous television, travel to and extensive knowledge of other Latin American countries was still rare), and indeed sexual (and not only for the more experienced and overtly womanizing Alberto).”5

At the outset of his journey, Che was a medical student in his early twenties, driven by fervent curiosity. He had yet to become the Che known as a Marxist revolutionary and military theorist—the one commonly recognized through the iconic image with a beret and an imposing look that has been widely appropriated by the culture industry. However, as certain events unfolded along the duo’s journey and the observation of Latin America took shape against the backdrop of spectacular landscapes, rich natural resources, cultural heritage, and pervasive poverty and class divide, Che’s initially touristic motivations transformed into those of examination and critical reflection. This transformation was in part brought about by the actual hardships that Che and Alberto went through after they left behind metropolitan Buenos Aires. Along their journey, the duo encountered challenges such as losing the broken motorcycle, running out of money, and facing difficulties in finding food and shelter. Only after completing one third of their journey, Che writes,

We had come to a new phase in our adventure. We were used to calling idle attention to ourselves with our strange dress and the prosaic figure of La Poderosa II, whose asthmatic wheezing aroused pity in our hosts. To a certain extent we had been knights of the road; we belonged to that long-standing ‘wandering aristocracy’ and had calling cards with our impeccable and impressive titles. No longer. Now we were just two hitchhikers with backpacks, and with all the grime of the road stuck to our overalls, shadows of our former aristocratic selves.6

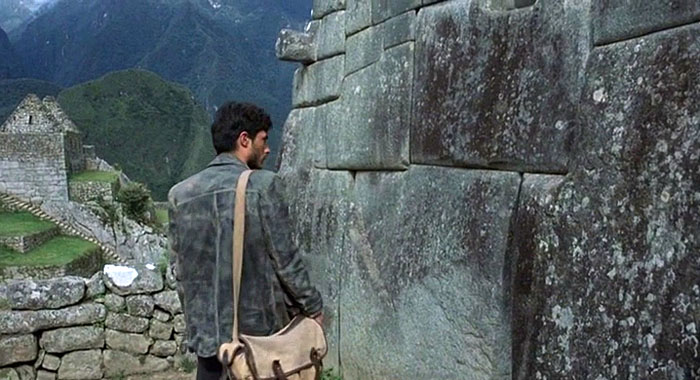

Transformation, then, emerges as a main theme in both the diaries and the film. In the film, the Machu Picchu segment serves as a visual climax, contrasting Che’s earlier observations of existing economic hardships in the region, particularly among the Indigenous population, with the grandeur of the pre-Columbian civilization of the Incas. The picturesque representation of Machu Picchu, juxtaposed with depictions of adversities such as homelessness and unemployment, highlights the divide between the present and the past. The film relies on this contrast to foreshadow the development of the future revolutionary leader as Che encounters the ruins with astonishment.

After engaging in friendly conversations with Indigenous people about their daily challenges and efforts at resistance, and passing by the impressive Peruvian landscapes, Che and Alberto are seen climbing towards Machu Picchu. The camera follows them as they ascend, momentarily leaving them as it moves up to focus on an isolated green mountain peak immersed in fog. Notably, the sound editing of the scene is marked by a change, where the lyrical tunes of remote forest creatures are heard over the mountain peak, adding a mysterious effect that alludes to a bygone era. The duo reappears as they step into and face the site expanding in front of them. Leaving Che’s stunned face, the camera captures Machu Picchu as Che and Alberto, now with their backs to the camera, meditate on the ruins in awe and silence.

Che’s mesmerized stillness in front of the spectacular Machu Picchu is a moment in which the misery of the present collapses into the grandiosity of the past. However, this impression does not persist in the remaining scenes of the Machu Picchu sequence. In an abrupt change of sentiment, Che is seen exploring the site along with Alberto and posing for photographs in front of the ruins like a tourist before reflecting on the divide between the past and the present in his diaries: “The Incas knew astronomy, brain surgery, mathematics among other things, but the Spanish invaders had gunpowder. What would America look like today if things had been different?”7 In response to Alberto’s suggestion to start an Indigenous party, encourage the people to vote, and reactivate the Indo-American revolution, Che responds: “A revolution without guns? It would never work…”8 He is then shown wandering alone in Machu Picchu, gazing closely at its stone blocks, and pausing one last time to capture a landscape view of the site, asking “How is it possible to feel nostalgia for a world I never knew?”9

In Che’s diaries, explicit references to tourists’ reception of Machu Picchu highlight the site as a major attraction. In the film, however, Machu Picchu is portrayed as an empty landscape explored solely by Che and Alberto. Elevating the site to a realm beyond the here and now, this peculiar cinematic choice reimagines Machu Picchu as a setting against which the enchanted Che and Alberto become the ones discovering the ruins and its true meaning in relation to current social conditions. The uninhabited Machu Picchu, standing in timelessness, serves as a picturesque backdrop for a climactic sequence that portrays Che’s political awakening, anticipating his transformation into a future military leader. In Che’s diaries, however, Machu Picchu does not itself play such a pivotal role. Instead, it is the entire section on Peru that acts as a climax, where the convergence of cultural heritage, indigeneity, colonial impositions, and socioeconomic disparities becomes a provoking force, compelling Che to contemplate the past in relation to the present. In Che’s exploration of the Inca lands, Machu Picchu serves as a puzzle piece, working in juxtaposition with Cuzco and Lima. This combination prompts Che to incorporate into his diaries an investigation of the Pre-Columbian history of the Inca civilization, which is informed by its resistance against the Spaniards.

Acknowledging the magnificence of Machu Picchu, Che points out in his diaries that “the site whose archaeological and ‘touristic’ significance overwhelms all others in the region is Machu Picchu, which in the indigenous language means Old Mountain. The name is completely divorced from the settlement which sheltered within its hold the last members of a free people.”10 Instead of providing a sensational account, Che provides a short but detailed description of the site as part of his description of Inca lands with references to Inca mythology and sociopolitical and architectural expansions of Inca civilization, concluding that:

[i]n reality it hardly matters what the primitive origins of the city are. It’s best, in any case, to leave discussion of the subject to archaeologists. The most important and irrefutable thing, however, is that here we found the pure expression of the most powerful indigenous race in the Americas – untouched by a conquering civilization and full of immensely evocative treasures between its walls. The walls themselves have died from the tedium of having no life between them. The spectacular landscape circling the fortress supplies an essential backdrop, inspiring dreamers to wander its ruins for the sake of it; North American tourists, constrained by their practical world view, are able to place those members of the disintegrating tribes they may have seen in their travels among these once-living walls, unaware of the moral distance separating them, since only the semi-indigenous spirit of the South American can grasp the subtle differences.11

Che’s reflections on Machu Picchu and its Pre-Columbian history occasionally adopt a romanticizing language, despite acknowledging the fact that the Inca themselves were a conquering empire. Yet, these contemplations represent more than just a nostalgic fascination with Inca ruins; they embody an expression of inquisitive observation. His study of the past in relation to the present enhances a transformation that had been provoked by earlier moments of social awakening along the journey, including an encounter with a persecuted communist couple in search of work and witnessing the workplace conditions of miners in Chile.12 The visual depiction of the enchanting Machu Picchu in the film serves as a cinematic device to underscore a plot centered around Che’s transformation throughout his journey. The emphasis on Che’s astonishment before the spectacular ruins and his casual indulging in its attractions offers an insight into the person standing behind the impenetrable figure of a revolutionary leader. However, the sequence falls short of conveying Che’s scrutiny of the historical Machu Picchu, as evidenced in the pages of his diaries, which was part of a larger effort to understand and address the existing struggles in the region and develop revolutionary courses to tackle them. This shortcoming, marked by the picturesque representation of the Inca ruins as a backdrop for Che’s contemplation of the past, reduces Machu Picchu to its allure and attraction as it contributes to a pop-cultural portrayal of a cultural icon’s transformative expedition.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. Ernesto Che Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey (Ocean Press, 2003), 32. Four decades after the events recorded by Che in his diaries, the book was first published in Spanish in 1993 as Notas de Viaje by Casa Editora Abril in Havana, Cuba, and in English in 1995 by Verso Books. Directed by Walter Salles in 2004, The Motorcycle Diaries is an adaptation inspired by the book. ↩

2. Walter Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries (2004; FilmFour and BD Cine).↩

3. Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries, 117.↩

4. Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries, 2004.↩

5. Neil Archer, The Road Movie: In Search of Meaning (New York: Wallflower Press, 2016), 54.↩

6. Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries, 67-68.↩

7. Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries, 2004.↩

8. Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries, 2004.↩

9. Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries, 2004.↩

10. Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries, 108-109.↩

11. Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries, 111.↩

12. These encounters are portrayed in the film as well.↩